Life In Berlin in 2024

Or, No Trick To The Rain

I can tell you about the Berlin I experienced. It’s funny, in sitting down to write about it, I feel I have a poor grasp of the place despite having lived there for 3 months. It’s a city whose reputation proceeds it, and ultimately this does it no favors. For whatever you end up visiting, it won’t be the punk stickers and graffiti tags acting like advertisements on freeway overpasses. It won’t be the grainy footage of David Bowie’s flat in the late 1970’s, a shelter nestled right up against the U-bahn where he wrote Heroe’s in a summer before the Wall fell. No, Berlin today is more than the anti-Manhattan we’ve all been told. And when you’re here, in its streets and living this life, these two impressions will become difficult to resolve. At least they were for me.

The grayness is totalitarian and the S-Bahn comes at 8+ minute intervals (need I say more). The buildings are stucco-nightmares that don’t breath. It rains, and when it doesn’t you watch the sky anyway with anticipation––for months, sometimes––a low-grade anxiety on simmer inside you always. In Berlin you’re always anticipating, as in Berlin the ground is always shifting beneath your feet. Berlin dances and she shivers. Berlin changes. She is change.

And I suppose this is the good. It seems my arguement may be slipping here. Yes, despite her leaden habits and dour charms, Berlin still finds ways to cram new ideas into old forms.

II

But I’ve noticed that at some point changing becomes changing. You hear about this repeatedly in the stairwells and bars of Berlin, told by faces that look like they’ve been around long enough to know. It’s what I can speak to personally having witnessed in Brooklyn, and have heard reports of in LA, Barcelona, Paris, and Amsterdam. These places are turning––places that once harbored something, now only harbor those people who came looking for it once word got out.

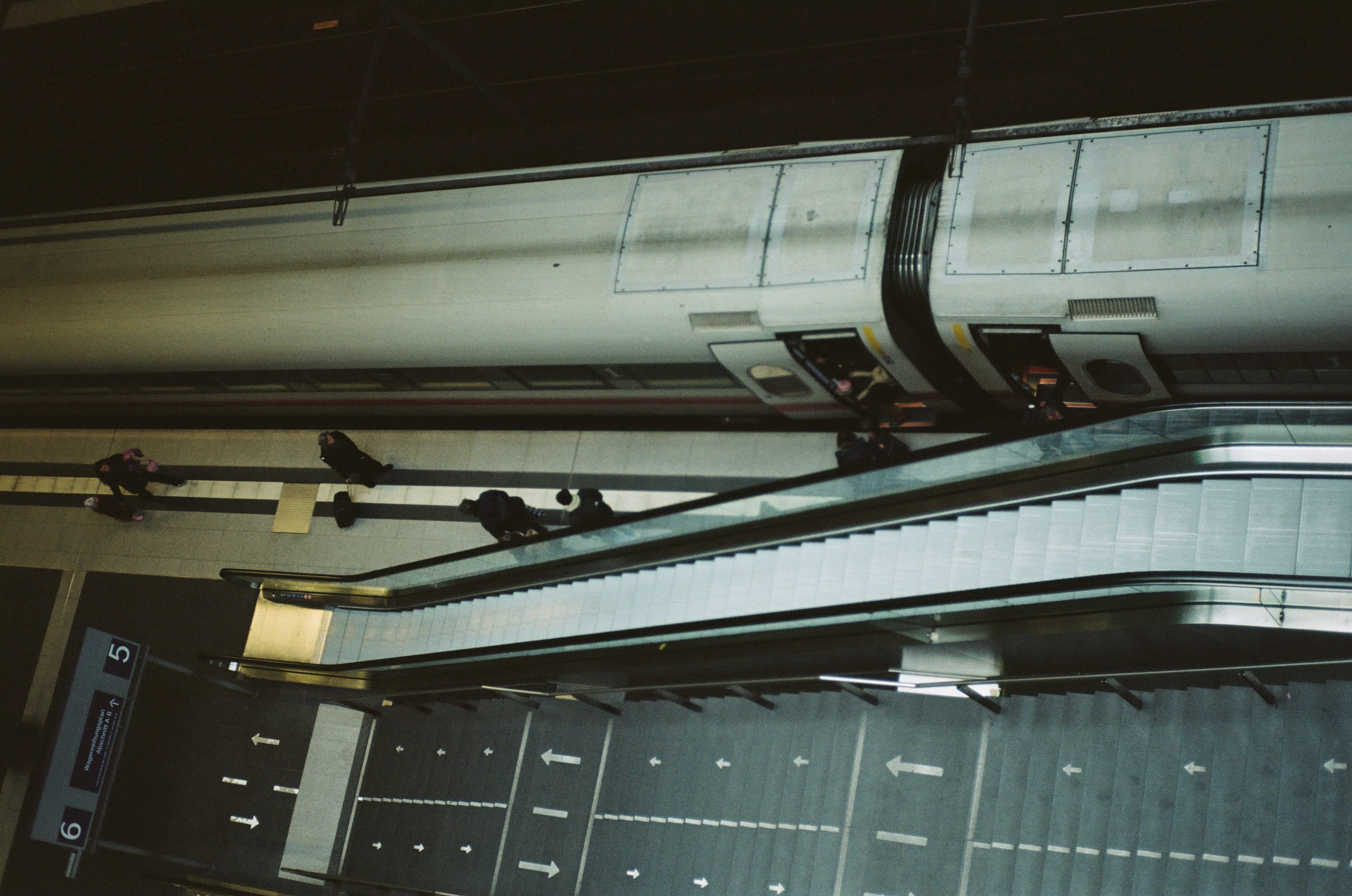

And writing this, I admit I came in on that wave of people looking for something in Berlin. I came on the algorithm’s infinite recommendation, for a city with a Wes-Anderson-worthy subway system and a warm gloominess. The promise was proferred that in these streets the down-and-outs, the financially hauranged, the misfits, the imposters, the gifted, the wannabe’s, etc. might have a piece of that good-ol’-fashioned belonging. And so I sent it. I bought my ticket, booked my room, and burned jet fuel across half the globe. But then you get here and realize a city isn’t a yellow subway car or a raincloud. It’s just you, all over again, in new surroundings. Colder surroundings. And so standing on Alexanderplatz and looking up at the clouds, at the underwhelming Soviet architecture, at the enormous chrome Mercedes Benz logo swivelling like a lunatic from the top of the Europa-Center, you end-up thinking, well, is this it? There’s no trick to the rain.

III

This underwhelming landing was perhaps a result of how the city has changed, but more than likely is simply a casualty of my personal preferences. Regardless, Berlin is changing:

Rents are up across the city and finding a flat even if you can afford one has become nigh impossible. The old guard are moving out as a result––going to Leipzig or France to raise their children. A good friend of mine, a quite successful musician who loves the city, was having difficulty remaining in Berlin on account of housing dilemmas despite his great wishes to. He of all people, who this city was seemingly designed for.

And this is perhaps what makes Berlin so tough to square with its iconoclastic image. In opening its doors, Berlin’s character––what it is famous for––has quietly begun to let itself out.

IV

To be truly cosmopolitan is to be nowhere? Beneath slate skies, you contemplate this. Situated between Soviet tower blocks, you hold your beer or cider or wine glass in the warmth of an apartment party. You find yourself speaking with an infinite rotation of other hopeful young artists. They are so kind, so talented, so emotionally intelligent. They put their songs up on Spotify like you do and play at Kindl Stuben on Sundays. You’ll see them there, first from the safe vantage point of the crowd, and then with a hand held over your eyes to block out the lights from the stage.

And so in Berlin you find you can meet only yourself. Just as you might in Brooklyn, Atlanta, Oakland, or Austin. And while this makes for a marvelous community, it’s one ultimately without polarity. And it’s very hard to fall in love with anyone or any place without a healthy bit of tension.

V

You’re no doubt grumbling at this point and think I’m a scrouge. I’ll say it––I’m a scrouge. My honest opinion here may be unwanted. But ultimately my hope is not to slander these talented people who have come to Berlin to pursue their passion, even as they arrive in swelling numbers. For they are truly wonderful & worth celebrating:

A closing example:

In Berlin, I have a friend named Sophia. She’s from Stuttgart. It’s a long story of how we met (one I’ll spare you), but I’m ultimately glad the stars aligned and we were able to persevere towards knowing eachother. In April, they have Gallery Week in Berlin, where all the gallery’s en-masse throw shows & open their doors to the weary crowds still shrugging-out of their heaviest coats. Sophia texts me––she’s hip to this sort of thing and we decide to do the circuit.

We walk, the sun is out, the day is nice, the trees green. We stop in for a cappucino at a place that makes tofu into desserts. Somehow the coffee here is good. She tells me about her journalism internship and her boyfriend and I listen while leaning my head back to catch a bit of warmth on the bench outside. When it’s my turn to share I go on about my usual dramas. Then we keep walking.

We see some decent art that day, paintings I promise myself I’ll remember and then promptly forget. In one spot we bump into a friend we’d made the week before, working at the gallery she said she was. In Berlin things like this happen––people are temporally where you’d expect them. She takes a break from manning the phoneline to walk us down to the exbihit floor:

“This one here,” she says, gesturing to a centerpiece, “is printed on a type of metal that is actually...”

I couldn’t for the life of me now remember what type of metal it was, but our friend’s statement was illuminating and this piece of reflective crap hanging on the wall only seconds earlier became suddenly––if not profound––at least something interesting enough to ellicit the thought, “wow, this is something special.”

We walked out onto the street then and I took this photo of Sophia. Sophia, I hope you’re still playing your guitar.

VI

The best of Berlin is in these moments, and these alone are reason enough to visit. Don’t go for the architecture, or the stupid subway system. Go for these wonderful displacers––these people who still come to the city with the express interest of making art. It’s an immigrant profile I wouldn’t wish on any municipality, economically speaking, and yet one I value tremendously in this instance. And so, even with the 90’s crowd heading out, and even with the rents approaching Parisian prices, as the city changes its spirit survives in these new faces.

D.C. 1/28/24

Go Home ︎︎︎