The Room of Yourself

In Mumbai & New York

When he arrived in Mumbai, India, he was coming off a stint of 5+ years living in a monastery at the top of Mount Baldy. Every morning, he’d wake 15 minutes before 4 AM to smoke a covert cigarette and drink a black coffee under the cover of darkness. Then it was up to the hall for tea served in silence, then meditation, chores, walking meditation, and other programs. It was a lifestyle as much uncorrupted by thought as it was rigorous in its physical demands: the monastery was exposed to the elements on all sides, and between the rows of seated meditation takers patrolled monks with staffs, who––less than gently––would “correct” any sitters not in proper form. Most 20 year olds wouldn’t have cut it, and he was already well into his 60’s. And truth be told, if he was honest with himself, he wasn’t cutting it anymore.

Sitting with his Zen Master one evening, sharing a cognac as they sometimes did, he told the 90 year old monk after a pause, “Roshi, I’m going down the mountain.” There was a further pause, this time hanging on the far edge of the precipitous. After a great length, Roshi finally replied:

“For how long?”

“I’m not sure,” he admitted, and in this answer revealed he had no definite plans to return.

Unhappiness should seem an odd companion for a life lived without dwelling in emotion, and yet it had sought him out. He had come to Mt. Baldy with the hope of becoming well-sealed against the human elements, and yet now he was beginning to realize that no one can become completely well-sealed. Unhappiness will necessarily get in, and though the quantity may be small at first, it will collect. Living a life of austerity (for there is little comfort in a cold, mountain view) had necessarily made him a basin for the stuff. He was not unhappy in the trivial sense. He was battling a deep depression. Even more so then when he’d arrived.

Before he’d arrived, he’d spent years living in what he called The Life of the Appetite (fame, drugs, sex, etc.), which had driven him to such a peek of horror he’d eventually sought sanctuary in Zen. He’d come with the wish only to be humbled, to feel empty such that inspiration, or light––or maybe they’re the same thing––could chance to fill him. This was a lifelong obsession of his, if one he only sought every several decades, and then often as last resort: the will to become a space for something better.

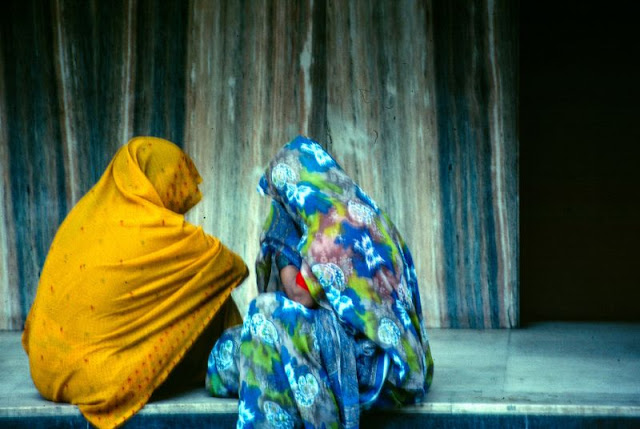

Mumbai, India, 1995

After coming down from the mountain however, in 1998, he chose a new direction. He flew, one way, to India. Walking between the street vendors and car horns of Mumbai, passerby’s would notice a man in a silk black shirt tucked-in to clean beige slacks. He looked like a romantic lead or a man who spent his summers on yachts. He took a small room at the Kemps Corner Hotel, where he had a window and not much else. And while in Mumbai, he began visiting the Satsung of a teacher, Ramesh Balsekar, whose books he’d come across while in America and had resonated with him. Ramesh was a retired bank president who had come to spirituality later in life; he hosted meetings now in his apartment that invariably followed a meditation/lecture/question format. Our visitor’s was one of the few western faces amongst the crowd, and yet he slipped in easily enough. In India, he was unknown. When stopping into a local music store once for example, he asked the sales clerk if they had any of his records. The clerk had to check in back, and only then returned with a box mislabelled “Easy Listening”.

Mumbai, India, 1995

Mumbai, India, 1995

And yet something was catching, and something old coming loose. In taking this simple routine of meditation, daily lunches with his cab-driver in the city’s dining halls, and ruminations in his room at the Kemps Corner without company, he felt for the first time––not only since Mt. Baldy, but in his life––the stirrings of happiness. The waters were going down, and as much as this perplexed him, he tried not to think about it. It’s sometimes best to accept a gift, and not ask by what means it has come to you.

He stayed in India for over six months before returning to his home again in Los Angeles. He would visit several more times in his life, to sit quietly and listen at the foot of the old banker in his nondescript apartment at the top of a nondescript tower. Ramesh turned most devotees away after a while, saying to them something to the effect of “go on now, don’t you have something to do with your lives?” But he let our friend stay-on in some unspoken agreement. Perhaps he could see he was serious. This man who was, after all, an ordained Buddhist monk.

The man I’m writing about is Leonard Cohen. There’s no advantage in my hiding his name from you, only that it makes for a better story.

II.

Recently, I spent three days living with a friend as I was between apartments. The first night I spent on an air mattress with only my coat draped across me as protection against the cold seeping in through the apartment’s thin walls. The following night a friend took pity and lent me their blanket. I slept better, but come morning still looked cratered. My face hung. My complexion was mummified. I was all worn-out.

For me, three days spent in anyone’s company is enough to wear me out. My social battery lasts about 3 hours, and on this particular occasion it was being tested beyond operational limits by the sheer social stamina of my host. Hers is an energy I admire if fail to understand completely. I wonder privately if it costs her something––that if behind closed doors she makes some compact with herself to keep the whole thing going. But then watching her sprawled out on the bedroom floor next to her roommate––Lauren––who’d just come in the door after an almost two day flight back to NYC from Hong Kong, I realize I must be wrong. Lauren is depleted, understandably, and Kate says she is too, so much so that she can’t go out for dinner with their friends. But then she’s still making jokes, still goes on to make her own dinner, is still herself.

Kate has a startling amount of energy.

Kate has a startling amount of energy.The point of all of this is to say that after three days of constant company, I am not still myself. Or perhaps I have become my true self, as we sometimes do under duress, in which case I have work to do. Regardless, in the light of my fatigue my social survival tactic has become only: have the next thing out of your mouth make sense. And even this low bar I’m failing to clear increasingly often. Whenever it is my turn to speak, to perform, the voice in my head whispers: They’ll see right through you.

My actual voice, in a dead give-away, betrays this. After constant conversation, it’s worn itself away to a whisper. And when I use it I don’t like the words I chose, or how they string themselves out in sentences. Everything is effortful, everything contrived. Lord, I’m an ass, I think to myself. And at the end of my three days of being myself publicly, I wanted to vanish. I want to bail-out, to quit. In the moment I’m having this conversation most acutely with myself, I’m doing the dishes. Washing a colander. Blue plastic with a million tiny holes in that instant filling with water. And sick of everything, I look at the thing, and decide just to look at it. No need to focus on it, no need to make an exercise out of it and make things difficult. Just look. And so I look at the colander.

And it’s as if, momentarily, I’ve stepped out of the room of myself. Within the newfound quietude, now unincombered by the contest of my mind, the colander shines & becomes suddenly the most beautiful thing.

III.

I think the exhuastion we face in sharing an apartment, a house, a partnership, a life, etc., comes not from the company we keep but from the self-important task we take-on of being ourselves. In this we really drag-out the finery: the attention we pay to the words we say, how we respond to what is said to us, how we dress, how we do our hair, the tone we take, what we avoid, what we joke about, hold sacred, chose to forgive. Etc.

And as the complexity of this calculus mounts, and as it depletes us necessarily such that we find ourselves operating more and more off our backfoot, its easy to find ourselves in hell. Yes––the onerous task of being ourselves publicly is a one way trip to hell. The hell of vanity, the hell of inadequacy, the hell of self-pity, and then all the resulting judgements. They all have heat enough to cook us.

With my nascent awareness of this blossoming, for the rest of my trip I try, whenever possible, to drop the whole game and simply look at the colander: To listen to what my friends were saying. To savor my food. To mop up spilled water. Etc. And while I was successful in this less than 1% of the time, my hope is that even in those small snatches I was a little less insufferable to share an apartment with. For our unhappiness is never truly ours alone––we always bring it into the room with us.

Outtings with friends.

IV.

With respect to Leonard, I wonder about his own unhappiness and how its severity shifted from meditating on a mountaintop in America versus in a crowded city abroad. In Mumbai, Cohen meditated, but he also fell in love with the women he passed on the street, and played his guitar in his room. And while he also did these things in America, in India, he got to do them without being Leonard Cohen. Even if he’d wanted to be Leonard Cohen, he found himself in the peculiar reality of being absolutely no one. Anonymous. A slightly sunburned face amongst a sea of other faces, numbering over 12 million.

When you’re famous, I think, you’re always sharing an apartment. People are always looking at you, and you’re always trying to decide (in the hallway, in the kitchen) how to act. In India, suddenly he wasn’t famous. And this gave him full license to turn on his powers of perception, honed after years of songwriting & meditation, without fear that in a moment he might have to turn them inwards. (How should I answer this interviewer’s question? Am I being Leonard Coheny enough?) As such, happiness stole over him and from that point on remained with him––unquestioned if never unappreciated.

No life-long takeaways remained after my stay with a friend for three days. I think however, at the end I got things right. In my last twenty minutes or so, sitting at her kitchen table and eating a can of reheated beans before going out the door, I tasted my meal. It wasn’t good, but it wasn’t bad either. I had a long trip ahead––a bus-ride to DC that would deposit me in the middle of the night. An apartment from there I hadn’t seen, in a part of town I wasn’t familiar with. It was closing-in on freezing outside as the sky sealed over in dark. But for now I was here, and in being here, the anxiety wasn’t percolating as strongly as usual. Standing, I collected my things, and said my goodbyes. My friend walked me to the elevator. I pressed the button, and feeling the lurch downwards, and the beginning of my trip, realized thankfully I wasn’t in hell.

D.C. 1/21/24

All Images of Mumbai Courtesy of Vintage Everyday

Go Home︎︎︎